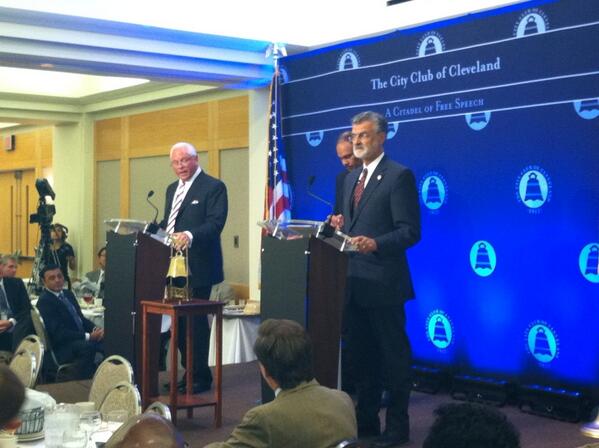

Frank Jackson saved his toughest lines for the end. With an anger he’s rarely shown since his 2005 campaign, he ripped into challenger Ken Lanci’s reason for running for mayor at today’s City Club debate.

In his closing statement, Jackson teed off on Lanci’s oft-stated motivation, that the millionaire businessman decided to serve others after a near-fatal heart attack.

“When you face these challenges… from an ivory tower and just decide to move back to Cleveland because you believe you have a burden, you’re not going to get the result you need,” Jackson said.

For an hour today, Jackson and Lanci sparred on crime and education, the big two issues of any mayor’s race. Lanci aimed a blunderbuss at Jackson, calling the mayor a failure at both. He quoted Jackson lines from his 2005 campaign against Jane Campbell.

“We are worse off than we were four years ago,” Lanci said, echoing Jackson. “If I don’t restore hope to the ailing city within 200 days of taking office, I will consider myself a failure.”

In his opening statement, Jackson responded calmly with figures about City Hall spending in city neighborhoods. But by the end, he was worked up, in full populist mode.

Something about Lanci really gets under Jackson’s skin. That a rich businessman would move in from the suburbs to run against him rankles him. It gets him going on a favorite point, about “ivory tower” folks who don’t live working-class struggles. (“Ivory tower” usually means academia -- Jackson is really saying Lanci is acting out of noblesse oblige.)

“It is a contradiction of terms to empower those you intend to oppress,” Jackson said in his closing. “When someone is looking to feel good because they help somebody, that means that relationship always has to be in that way, where you’re in need, in order for them to feel good.

“I don’t feel good. This stuff is painful because I have to live it every day. It is painful when my wife, and my children, and my grandchildren, and their friends have to deal with this on a daily basis.”

Lanci blasted Jackson for the Cleveland schools’ F on the latest state report cards and declared Jackson’s old transformation plan and new school reforms failures. He also attacked Jackson for championing the school levy last year.

“Putting $70 million into the system, from people who could least afford it, is not going to get results,” Lanci said. “We have to mentor our children, and provide the leadership students don’t get in their homes.”

Lanci may have a point -- his idea of an enormous city-wide mentoring program reminds me of all-encompassing efforts, such as Promise Neighborhoods and the Harlem Children’s Zone, to improve kids’ academic achievement by improving the rest of their lives. But mentoring programs are paternalistic by definition, and Jackson pounced on that.

“It’s amazing -- children are the problems in school,” Jackson said. “Mothers being unmarried are the problems. It’s condescending and disrespectful, and it has a tone of disdain. You cannot serve those you disdain.”

Lanci tried to recover. “It’s disrespectful for the people of Cleveland to live with a failed school system,” he said.

But he struggled with a question from an audience member who noted that some have praised Jackson’s school plan as a national model. Lanci answered by quoting a teacher’s complaints about 100-degree classrooms in a heat wave and district staff jobs with jargony titles.

On crime and cops, the debate turned, as usual this year, on state attorney general Mike DeWine’s contention that last November’s 60-car police chase and fatal shooting was the result of a “systemic failure” in the police department. Moderator Rick Jackson brought up the quote, noted that Lanci got the police union’s endorsement, and asked him where he stood on the November incident.

Lanci repeated his campaign pledge that he’d fire safety director Martin Flask and police chief Michael McGrath. Then he went further, promising to let the police union pick the top candidates for chief for him to choose from. It was an attempt to blame the uncontrolled chase on the department’s leaders, not the officers who violated policy by joining the chase, and Jackson jumped on it.

“When [the police] union president [was] asked whether their opposition to the chief was because he was holding them accountable, he said absolutely so, that’s the only reason he wants him fired,” Jackson asserted.

“The systemic failure was not with the Cleveland police division,” Jackson argued, then turned to an attack on DeWine. “The systemic failure was with the attorney general’s office, denying due process and civil rights to the two victims. I’ve never heard you [Lanci] or the police union mention the two victims who were denied their due process and civil rights. And as a result of that, those officers are denied due process, because there’s no way in which even they can have a fair criminal hearing in regard to this, because it wasn’t done properly.”

The candidates' arguments showed how Cleveland can’t move past a simplistic either-or debate about the November chase and shooting. One side blames the leadership, one side the officers. No one ever holds both accountable.

The debate revealed more of Lanci’s platform: He said he wouldn’t continue the mayor’s attempt to develop the lakefront, that Cleveland has more urgent problems that trump building hotels. Instead, he said he’d focus on bringing container shipping, ferries, and lake cruise ships to the port.

In the debate’s weirdest moment, an audience member asked if Lanci had really told the teachers’ union in a questionnaire that he would have the Hell’s Angels and Zulu motorcycle clubs mentor seventh graders.

Lanci said he wants to bring back Golden Gloves boxing city-wide, so sons of single mothers have male mentors.

“I’ve asked some of the motorcycle clubs to sponsor teams, to be able to help mentor these kids, to give them something to belong to other than a gangbanger. We have to stop them from feeding that system. Even the motorcycle clubs are afraid of them. Because they don’t want to kill anybody. They know the consequences. The gangbangers don’t know.”

In his closing argument, Lanci promised an end to “broken promises and platitudes.” He slammed the mayor for his failed attempts to build a gasification plant and use a street-lighting contract to attract a lighting factory to town.

Then came Jackson’s brutal close, in which he painted Lanci as a do-gooder running to feel good. “I don’t go to a place of tragedy with hot dogs and hamburgers, to be disrespectful and condescending to that tragedy,” he said. The mayor’s campaign aide, Chris Nance, says he was talking about Lanci’s appearance on Imperial Avenue, site of Anthony Sowell’s 11 murders, earlier this year.

As Jackson finished, supporters of his, sitting near me, rejoiced gleefully. “This case is closed,” one said.

Wednesday, September 18, 2013

Tuesday, September 10, 2013

Zack Reed, Jeff Johnson, Brian Cummins win city council primaries

Zack Reed may be spending 10 days in jail soon, but he beat his DUI conviction at the polls today. Voters in Cleveland Ward 2 rewarded the longtime councilman for his work instead of punishing him for drinking and driving. They gave him 83 percent of the vote in the city council primary election.

Jeff Johnson’s election gamble is paying off. He took 55 percent of the vote in northeast Cleveland’s Ward 10 against fellow councilman Eugene Miller, who got 39 percent.

Johnson, whose old ward was sliced up in redistricting, looks likely to thwart council president Martin Sweeney’s gerrymandering. Sweeney designed the awkwardly stretched-out Ward 10 to set up Miller for re-election. But Johnson, who served on council in the 1980s and returned in 2009, saw an opportunity to unseat the younger Miller.

Johnson, whose old ward was sliced up in redistricting, looks likely to thwart council president Martin Sweeney’s gerrymandering. Sweeney designed the awkwardly stretched-out Ward 10 to set up Miller for re-election. But Johnson, who served on council in the 1980s and returned in 2009, saw an opportunity to unseat the younger Miller.

The two councilmen, who will face off again in the Nov. 5 election, have both been damaged by scandal. Johnson’s political career seemed over when he served prison time for a 1998 extortion conviction, but voters seem to be accepting that he’s followed a path to rehabilitation. Miller’s troubles, smaller by comparison, are recent: an impaired-driving case, a voting-address snafu just referred to the county prosecutor, and embarrassing 911 calls.

Brian Cummins, councilman for the near West Side’s Ward 14, came out on top of a four-way race in first place with 31 percent of the vote. He’ll face challenger Brian Kazy, who got 26 percent.

Brian Cummins, councilman for the near West Side’s Ward 14, came out on top of a four-way race in first place with 31 percent of the vote. He’ll face challenger Brian Kazy, who got 26 percent.

Kazy edged out an aggressive candidate, Janet Garcia, for a spot in the runoff. Garcia, running in a ward that’s 41 percent Hispanic, argued for electing a Hispanic councilperson. She won the Democratic Party endorsement and campaigned in a white car covered with her name in giant letters. But another Hispanic candidate, former councilman Nelson Cintron, kept her from achieving critical mass. A pending felony case against her, in which she’s accused of assaulting a Westlake police officer, probably didn’t help either. (She has maintained she’ll be found not guilty.)

November victories by Reed, Johnson, and Cummins would shore up the opposition to Martin Sweeney's council majority. But in Hough’s Ward 7, a Sweeney supporter did better than some expected today.

Councilman T.J. Dow won 47 percent of the vote and will face an energetic challenger, Basheer Jones, in November. Jones, a former radio talk show host, poet and motivational speaker, got 27 percent, while former councilperson Stephanie Howse got 21 percent.

Jeff Johnson’s election gamble is paying off. He took 55 percent of the vote in northeast Cleveland’s Ward 10 against fellow councilman Eugene Miller, who got 39 percent.

The two councilmen, who will face off again in the Nov. 5 election, have both been damaged by scandal. Johnson’s political career seemed over when he served prison time for a 1998 extortion conviction, but voters seem to be accepting that he’s followed a path to rehabilitation. Miller’s troubles, smaller by comparison, are recent: an impaired-driving case, a voting-address snafu just referred to the county prosecutor, and embarrassing 911 calls.

Kazy edged out an aggressive candidate, Janet Garcia, for a spot in the runoff. Garcia, running in a ward that’s 41 percent Hispanic, argued for electing a Hispanic councilperson. She won the Democratic Party endorsement and campaigned in a white car covered with her name in giant letters. But another Hispanic candidate, former councilman Nelson Cintron, kept her from achieving critical mass. A pending felony case against her, in which she’s accused of assaulting a Westlake police officer, probably didn’t help either. (She has maintained she’ll be found not guilty.)

November victories by Reed, Johnson, and Cummins would shore up the opposition to Martin Sweeney's council majority. But in Hough’s Ward 7, a Sweeney supporter did better than some expected today.

Councilman T.J. Dow won 47 percent of the vote and will face an energetic challenger, Basheer Jones, in November. Jones, a former radio talk show host, poet and motivational speaker, got 27 percent, while former councilperson Stephanie Howse got 21 percent.

Monday, September 9, 2013

FitzGerald prepares to sue over 2005 Ameritrust purchase

The years of controversy over Cuyahoga County’s 2005 purchase of the Ameritrust Tower may be about to reach a climactic moment.

Cuyahoga County Executive Ed FitzGerald's law department is preparing to file a lawsuit over the controversial real estate deal. The county’s board of control voted today to hire two law firms as special counsel for “potential litigation related to the County’s purchase of the Ameritrust Complex.”

County law director Majeed Makhlouf says the county may sue the former Staubach Co., a former real estate consultant to the county, and Anthony Calabrese III, a lawyer who represented Staubach.

Prosecutor Tim McGinty may become involved in the case as well. The “primary avenue” for a suit, according to Makhlouf, would be an Ohio law that allows county prosecutors to sue for damages over a contract “procured by fraud or corruption” or to recover money “illegally drawn” from the county treasury.

FitzGerald has talked about suing Staubach, now part of Jones Lang LaSalle, since early 2012. He has complained about the $3 million the old county government paid Staubach over the Ameritrust purchase and the allegations Calabrese was involved in criminal wrongdoing related to the deal.

Cuyahoga County’s old government paid $21.7 million for the Ameritrust complex in September 2005 and spent roughly $23 million more on the project, including the $3 million broker fee, asbestos removal, and the purchase of a second parking garage. The new county government sold the complex to the Geis Cos. this year for $27 million, or a loss of about $18 million.

McGinty indicted Calabrese on corruption charges related to the Ameritrust affair this summer. The indictment claims that Calabrese got J. Kevin Kelley to give him “non-public information” from then-commissioner Jimmy Dimora about the pending deal, and that after the sale, Calabrese arranged for Kelley to receive a $70,000 bribe for his help. A county grand jury is also reportedly investigating possible connections among Dimora, Calabrese, and Vincent Carbone, whose company was the construction manager on the Ameritrust project. Calabrese has pled not guilty.

Rob Roe of Jones Lang LaSalle says the company has cooperated with all prior investigations into the Ameritrust transaction and will cooperate in any future inquires. "We believe our efforts on behalf of the County met the highest standards of quality and ethics that our clients have come to expect from us, and no one connected with any prior federal or County investigation into the transaction has ever suggested that they did not," Roe said in a statement Tuesday.

In an interview with me in spring 2012, Roe defended Staubach’s broker fee (which was shared with other companies) and its advice to the county (which was to lease the Ameritrust complex, not buy it). Roe said nothing about Calabrese’s conduct while representing Staubach appeared improper or gave him pause, and that Calabrese never talked about using any connections in county government to help Staubach.

A lawsuit now would come eight years after the controversial real estate deal. In fact, the county may be racing against the clock. If it files suit before September 30, it could avoid a legal battle over whether an eight-year statute of limitations applies.

The investigation of the deal has been long and complex, Makhlouf says. Now, with the federal corruption investigation mostly complete and the Ameritrust complex sold, the county is close to ready.

“This is a very important piece of litigation for us,” says Makhlouf, “but we couldn’t do anything that risked what we were doing in the sale of Ameritrust and the potential for the rejuvenation of that entire quarter.”

To assemble a case, the county’s lawyers have looked at the Jimmy Dimora trial, the federal and county indictments of Calabrese, county documents that federal investigators seized and have now returned, and an employment discrimination lawsuit against Jones Lang LaSalle that alleges senior management improperly destroyed records after learning about clients’ roles in federal corruption probes.

“It wasn’t the kind of investigation you went into, and there were all these records, and you went through them, and [found] the smoking gun,” Makhlouf says. “It was the type of investigation that needed many pieces to fall together from different places.”

The county hired business law firm Brennan, Manna & Diamond of Akron, and Giffen & Kaminski of Cleveland, which has business litigation and white-collar criminal defense practices. It was hard to find law firms who could help the county, Makhlouf says. Almost every local law firm had represented clients in the county corruption investigation, he says, and many firms did not want to sue a real estate broker because they see them as sources for referrals.

A suit under prosecutors' power to protect public funds is now easier because of the new agreement between the prosecutor and the law department over how they will split and share the job of representing the county in court. That law has no statute of limitations, Makhlouf says.

(Updated, 2:50 pm, to reflect the prosecutor's potential role, and 9/10, with details on the law firms hired and a new statement from Roe.)

Cuyahoga County Executive Ed FitzGerald's law department is preparing to file a lawsuit over the controversial real estate deal. The county’s board of control voted today to hire two law firms as special counsel for “potential litigation related to the County’s purchase of the Ameritrust Complex.”

County law director Majeed Makhlouf says the county may sue the former Staubach Co., a former real estate consultant to the county, and Anthony Calabrese III, a lawyer who represented Staubach.

Prosecutor Tim McGinty may become involved in the case as well. The “primary avenue” for a suit, according to Makhlouf, would be an Ohio law that allows county prosecutors to sue for damages over a contract “procured by fraud or corruption” or to recover money “illegally drawn” from the county treasury.

FitzGerald has talked about suing Staubach, now part of Jones Lang LaSalle, since early 2012. He has complained about the $3 million the old county government paid Staubach over the Ameritrust purchase and the allegations Calabrese was involved in criminal wrongdoing related to the deal.

Cuyahoga County’s old government paid $21.7 million for the Ameritrust complex in September 2005 and spent roughly $23 million more on the project, including the $3 million broker fee, asbestos removal, and the purchase of a second parking garage. The new county government sold the complex to the Geis Cos. this year for $27 million, or a loss of about $18 million.

Rob Roe of Jones Lang LaSalle says the company has cooperated with all prior investigations into the Ameritrust transaction and will cooperate in any future inquires. "We believe our efforts on behalf of the County met the highest standards of quality and ethics that our clients have come to expect from us, and no one connected with any prior federal or County investigation into the transaction has ever suggested that they did not," Roe said in a statement Tuesday.

In an interview with me in spring 2012, Roe defended Staubach’s broker fee (which was shared with other companies) and its advice to the county (which was to lease the Ameritrust complex, not buy it). Roe said nothing about Calabrese’s conduct while representing Staubach appeared improper or gave him pause, and that Calabrese never talked about using any connections in county government to help Staubach.

A lawsuit now would come eight years after the controversial real estate deal. In fact, the county may be racing against the clock. If it files suit before September 30, it could avoid a legal battle over whether an eight-year statute of limitations applies.

The investigation of the deal has been long and complex, Makhlouf says. Now, with the federal corruption investigation mostly complete and the Ameritrust complex sold, the county is close to ready.

“This is a very important piece of litigation for us,” says Makhlouf, “but we couldn’t do anything that risked what we were doing in the sale of Ameritrust and the potential for the rejuvenation of that entire quarter.”

To assemble a case, the county’s lawyers have looked at the Jimmy Dimora trial, the federal and county indictments of Calabrese, county documents that federal investigators seized and have now returned, and an employment discrimination lawsuit against Jones Lang LaSalle that alleges senior management improperly destroyed records after learning about clients’ roles in federal corruption probes.

“It wasn’t the kind of investigation you went into, and there were all these records, and you went through them, and [found] the smoking gun,” Makhlouf says. “It was the type of investigation that needed many pieces to fall together from different places.”

The county hired business law firm Brennan, Manna & Diamond of Akron, and Giffen & Kaminski of Cleveland, which has business litigation and white-collar criminal defense practices. It was hard to find law firms who could help the county, Makhlouf says. Almost every local law firm had represented clients in the county corruption investigation, he says, and many firms did not want to sue a real estate broker because they see them as sources for referrals.

A suit under prosecutors' power to protect public funds is now easier because of the new agreement between the prosecutor and the law department over how they will split and share the job of representing the county in court. That law has no statute of limitations, Makhlouf says.

(Updated, 2:50 pm, to reflect the prosecutor's potential role, and 9/10, with details on the law firms hired and a new statement from Roe.)

Friday, September 6, 2013

Campaign finance reform: an activist who won't give up, a county councilman who never understood

| Coleridge |

Cleveland.com got councilman Michael Gallagher to write a response. In July, Gallagher took the lead in arguing down the charter commission's proposal to give council the power to regulate campaign donations.

Sadly, embarrassingly, Gallagher's op-ed piece shows he didn't even understand what he and the council rejected. He spends the entire piece arguing against limiting the total amount of money any one political candidate can spend.

Coleridge sums up Gallagher's mistake with a headline on his blog: "Politician confuses political contribution limits with political spending limits."

County politicians have gotten checks for $25,000, $36,000, $50,000, $300,000, and $400,000 in the past. Once a candidate takes office, what sort of debt do they feel to the writer of checks that big?

Now ought to be the perfect time to ban jumbo-sized donations. Jimmy Dimora, the poster boy for county reform, testified last week before a grand jury about suspected illegal activity around the 2005 purchase of the Ameritrust complex. Dimora voted to buy the Ameritrust property from the late Dick Jacobs, who seeded Dimora's first campaign for county commission with a $36,000 check. The county sold the Ameritrust complex this year -- at an $18 million loss to taxpayers.

Coleridge still hopes the county council will change its mind on campaign finance reform. But what are the odds, when Gallagher doesn't even understand what's possible, and most councilpeople clearly want the issue to go away? It looks like there's only one way for reform-minded people to create a sane campaign finance system in Cuyahoga County -- a citizens' petition for a charter amendment.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)